How We Create Proper Drainage in Narrow Minneapolis Side Yards While Keeping a Functional Walkway

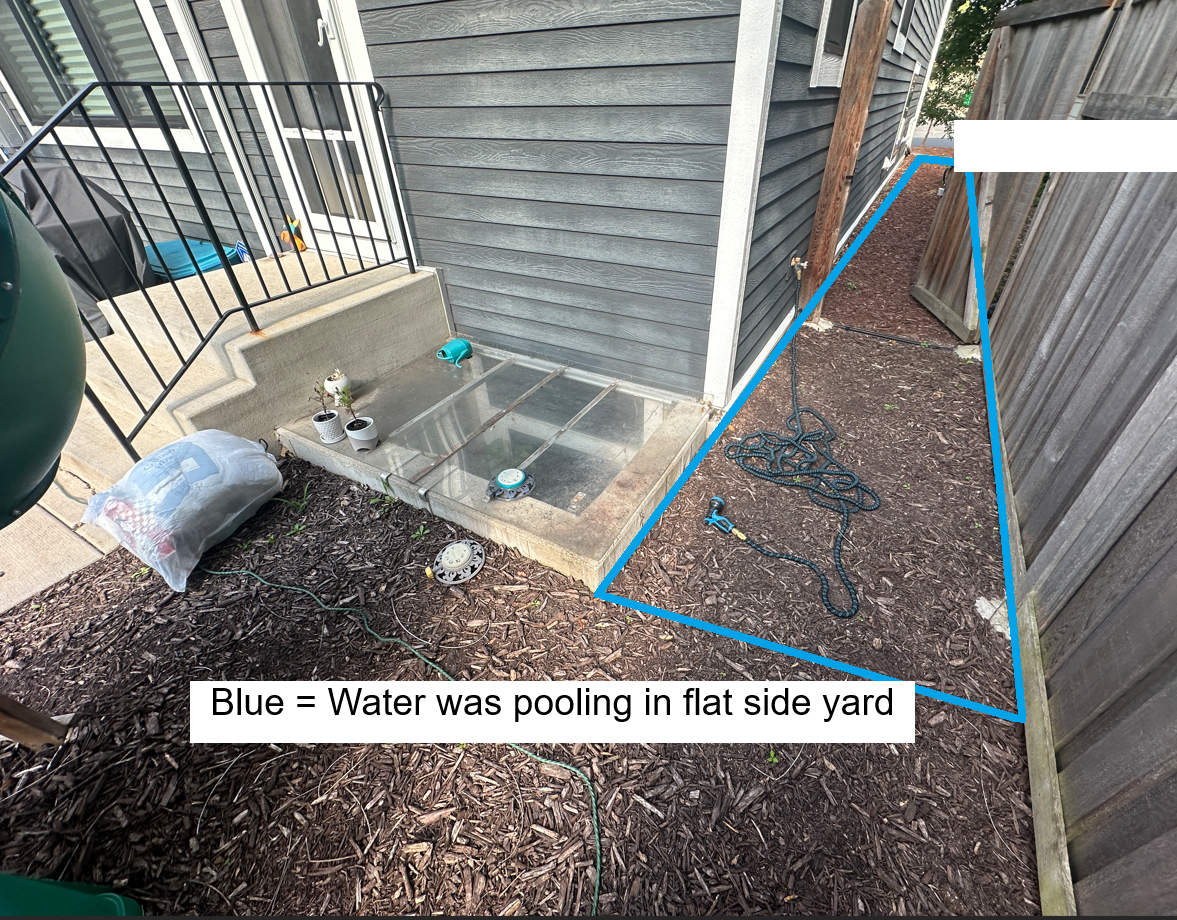

Homes in Minneapolis sit close together. Small city lots, not much room between houses. That tight spacing creates drainage problems when water runs off roofs, empties from downspouts, and lands in the 5 or 6 feet between you and your neighbor.

The goal is simple. Send water away from both foundations, toward the property line, out to the front or back yard. Actually doing that is harder than it sounds.

These narrow side yards aren't just drainage channels. They're how you walk around your house. Traditional fixes like swales can work, but carving a ditch into a space that's barely wide enough to walk through isn't always practical.

For these reasons, we often recommend French drains, also called drain tile, as part of a complete solution. This article explains how we used that approach to solve a side yard drainage problem in Minneapolis while keeping the area level and easy to walk through.

Why Drainage Problems Are So Common in Minneapolis Side Yards

Side yards in Minneapolis are narrow. Most are somewhere between 4 and 8 feet wide, sometimes less. These spaces traditionally include concrete sidewalks that were installed when the house was originally built, often in the early 1900s. Those older sidewalks are commonly 2.5 feet or 30 inches wide, built directly against the foundation.

After a hundred years, a lot has changed. The concrete has cracked or settled. The original pitch away from the house no longer works. In some cases, the sidewalk was removed entirely and replaced by a homeowner or a less experienced contractor who didn't account for drainage when regrading.

Other factors make the problem worse. One house might sit significantly higher than the neighbor's, which causes water to rush toward the lower foundation. Downspouts dump water into the side yard with nowhere for it to go. Soil settles over time. What used to drain fine now pools against the house.

Minneapolis soil is actually decent in a lot of areas. We dig into what we expect to be clay and find pretty good black dirt with a sandy base underneath. Drains well. That's usually a good thing, but not next to a foundation. Well-drained soil means water soaks straight down instead of running away. Gets into the basement.

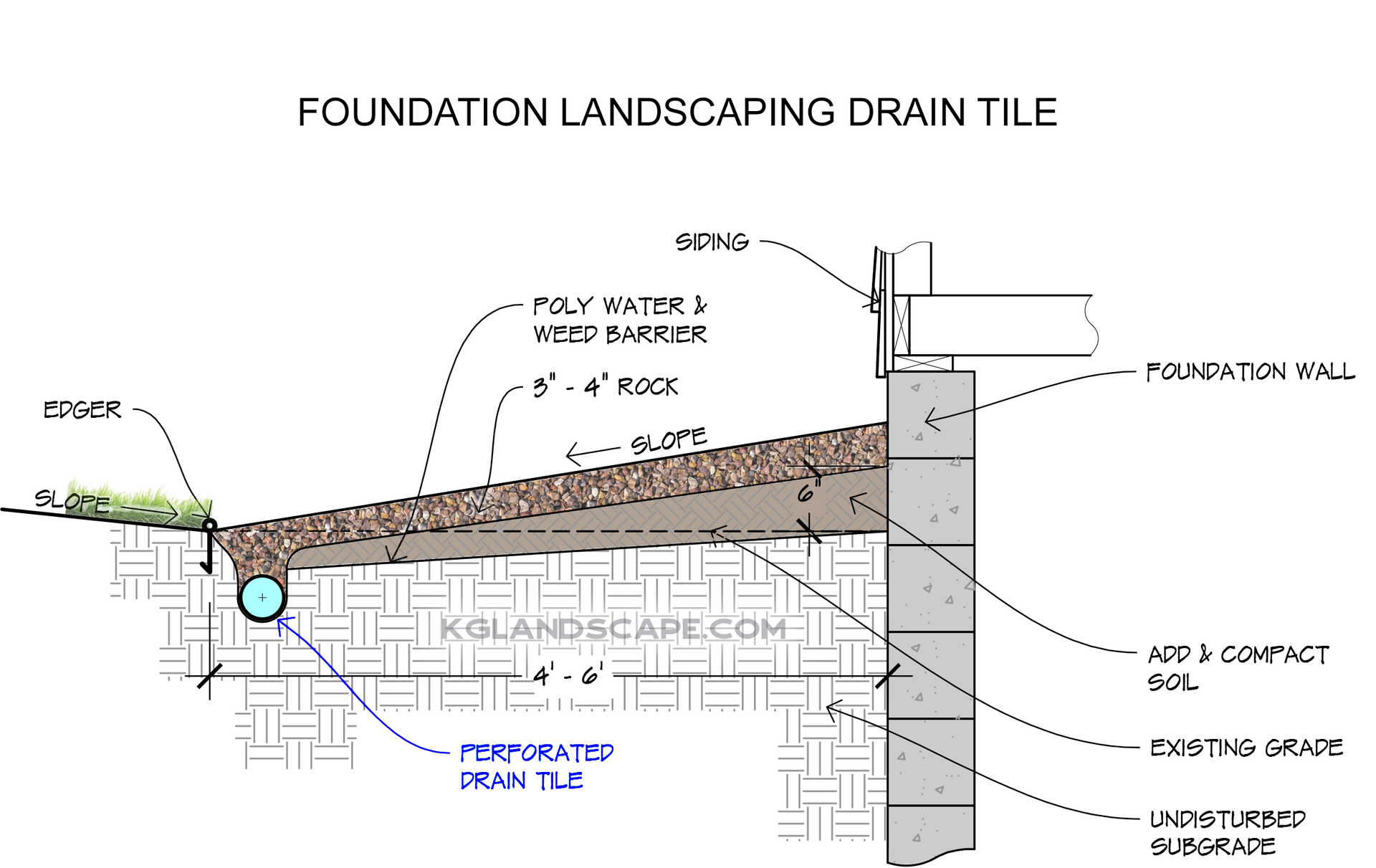

Proper grading needs to move water away quickly. The University of Minnesota Extension recommends a minimum slope of a quarter inch per foot, or about 1 inch over 4 feet, to help water sheet away before too much soaks into the soil near the foundation.

Mistakes We See All the Time

Concrete companies focus on concrete. The good ones pitch the new sidewalk away from the house. But that doesn't solve anything if the water has nowhere to go.

We've seen plenty of sidewalks installed correctly, sloped perfectly away from the foundation, dumping water into the side of a hill where it pools against a retaining wall. The concrete work was fine. Nobody thought about what happens after the water leaves the edge of the slab.

Narrow side yards with real drainage problems need someone thinking about the whole system. The underground drainage, the walkway surface, the finish grading. All of it. That's what we do, and it's uncommon in this market. Most companies pick one piece and call it done.

How We Solved It on This South Minneapolis Project

The homeowner's sump pump ran constantly. That's a sign too much water is reaching the interior drain tile. Sump pumps are supposed to be backup systems, not the first line of defense. If yours runs all the time, water is getting to the basement that shouldn't be.

This project had two parts: regrading the side yard so water pitched away from the house, and installing a French drain, also known as drain tile, along the foundation to collect and move that water out.

The French drain started at roughly 12 inches deep near the back of the house and sloped down to around 18 to 24 inches at the front corner. We also built 6 inches of fall into the foundation grading itself. Water hitting the ground near the house sheets away from the foundation, drops into the French drain trench, and flows out to the front yard.

After regrading and excavating the trench, we lined everything with heavy 8-mil woven geotextile. The fabric lets water sheet down the slope we created and run into the French drain instead of soaking straight into the soil.

[IMAGE: Foundation drain tile with liner below and 6 inches of slope.jpg]

[IMAGE: During Foundation Drain tile being measurement for slope with altim...]

Next, we installed 4-inch perforated drain pipe with a silt sock cover. The sock keeps fine particles out of the pipe so the channel stays open and functional over time.

We backfilled around the pipe with 3/4-inch clear rock. We use 3/4-inch stone rather than larger rock because it protects the pipe better. Larger stones can transfer force from foot traffic or equipment above and potentially damage the drain pipe below. The smaller stone distributes weight more evenly.

On top of the drainage rock, we installed 3/4-inch crushed trap rock as the finish surface. Crushed stone works well as a walkway material because the angular edges lock together and stay in place. Round stones like pea gravel shift and move when you walk on them, which is why we don't use pea gravel for applications like this.

The finished surface looks clean and functions as a level walkway. Water flows through the crushed rock, hits the geotextile liner, follows the grade down to the French drain, and exits completely away from the house.

Where the Water Goes

For this project, the French drain connected to a dry well we installed in the front yard. The dry well was already being built to handle sump pump discharge from the other side of the house, so we tied the French drain into that same system.

[IMAGE: dry well pic.jpg]

[IMAGE: covering top of dry well with fabric.jpg]

This is where the two drainage solutions overlap. The dry well collects water from multiple sources, holds it temporarily, and allows it to slowly absorb into the surrounding soil away from the foundation. By connecting the French drain to the dry well, we created a single unified system that handles both the side yard drainage and the sump pump discharge.

We covered another part of this same Minneapolis property in a separate case study that focused on grading solutions for the other side yard. That side used a swale instead of a French drain because it wasn't used as a primary walkway. The swale works equally well for drainage, but a French drain with a rock surface is better when you need the area to function as a flat, easy-to-walk path.

The Result

Water flows away from the house now. Sheets across the regraded surface, drops into the French drain, travels through the pipe, empties into the dry well out front. The sump pump runs maybe a quarter as often as it used to.

The side yard is level and easy to walk through. Crushed trap rock surface, drains instantly, no pooling, no mud. The homeowners use it every day to get from the back gate to the front without thinking about it.

That's the difference between fixing a symptom and solving the problem. A new sidewalk alone wouldn't have done this. A drain pipe alone wouldn't have either. Everything had to work together.

When to Call a Drainage Professional

Tight lots and complicated grading don't fix themselves. And hiring separate contractors for the walkway, the drainage, and the landscaping usually means nobody's thinking about how all the pieces connect.

We approach these projects differently. The drainage system, the hardscape, the grading, it all gets designed together and installed by one crew. That's the only way to make sure the water actually ends up where it's supposed to go.

We've been doing this work for Minneapolis homeowners since 2003. If your side yard pools water, if your sump pump never stops running, or if you've tried fixes that didn't last, a site evaluation is where we'd start.

Frequently Asked Questions

What's the difference between a French drain and drain tile?

The terms are often used interchangeably. Both refer to a perforated pipe installed in a gravel-filled trench that collects and redirects water. Technically, drain tile was the original term from when clay tiles were used. Modern systems use perforated plastic pipe, but the concept is the same. The Interlocking Concrete Pavement Institute and other industry resources use both terms to describe subsurface drainage systems designed to move water away from problem areas.

Can I install a French drain myself?

You can try. The trench needs proper depth and slope. The pipe needs to be bedded in gravel correctly. The fabric has to direct water where you want it. Most DIY French drains we see failed because the slope was off or the outlet wasn't actually lower than the inlet. Water doesn't flow uphill.

How long does a French drain last?

Twenty years or more if it's done right. The things that kill them: crushed pipes, clogged fabric, blocked outlets. We use 3/4-inch stone to protect the pipe, silt socks to keep particles out, and we make sure the outlet won't get buried or back up over time.

Will a French drain fix my wet basement?

It depends on why your basement is wet. If the problem is surface water pooling against your foundation, a French drain combined with proper grading can absolutely help. It reduces the amount of water reaching your interior drain tile and takes pressure off your sump pump. If the problem is a high water table or groundwater seeping through the floor, you may need interior solutions as well. A site evaluation can help determine where the water is coming from and what combination of solutions will work.

What's better for a side yard, a French drain or a swale?

Both work for drainage. The difference is usability. A swale is a shallow channel carved into the ground that directs water. It works well when you have enough width to create a gradual slope and the area doesn't need to be flat for walking. A French drain keeps the surface level because all the drainage happens underground. For narrow side yards that double as walkways, a French drain with a rock or paver surface is usually the better choice. You get proper drainage without sacrificing the ability to walk through comfortably.

About the Author

Kent Gliadon is the owner and principal designer at KG Landscape, a Minneapolis-based landscape design and build company serving homeowners across the Twin Cities for over 20 years. Kent studied landscape architecture and earned a bachelor's degree in Environmental Horticulture at the University of Minnesota, with emphasis in turf science and landscape design.

Ready to Start on Your Next Project?

Call us at (763) 568-7251 or visit our quote page.